The first English group to settle in what is now South Carolina was led by John Cabot in 1497. They claimed the area under King Henry VII. It was that claim that led to Charles I granting what was then called “Carolana” to Sir Robert Heath. However, Charles I was executed in 1649 and Sir Robert Heath had not settled the land by that time. Many English citizens showed loyalty to Charles II during England’s commonwealth period. When he gained the throne in 1660, there were 8 men who tried to claim rewards for their loyalty to him. Those men were: Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon, George Monck, Duke of Albemarle, Lord William Craven, Lord John Berkeley, Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper, Earl of Shaftesbury, Sir George Carteret, Sir William Berkeley, Sir John Colleton

In 1663, Charles II granted the eight Lords Proprietors the land that is now located in South Carolina, but was then simply known as “Carolina.” In 1665, once Heath’s successors’ land claims had been refuted, the grant was extended and revised.

Settlement plans were interrupted multiple times by the 1665 Great Plague, London’s Great Fire in 1666, and the war between the French and the Dutch. However, in August of 1669, more than one-hundred colonists set sail on 3 ships. Their captain was Joseph West. In November, under his command, they arrived in Barbados. Eventually, two ships went down due to poor weather, but the third, along with two new sister ships, arrived in what is now known as Bull’s Bay on March 15, 1670. That marked the beginning of South Carolina’s permanent settlement.

The first settlement in South Carolina was located at the mouth of the Ashley River. It was called “Old Town.” Each man who was over the age of 16 was given a headright grant of 150 acres. Females and males who were under the age of 16 were given 100 acres. However, many of the settlers chose to only live on 10-acre plots of land, in an effort to keep their homes more secure. In August of 1670, that proved to be a good tactic because the town was attacked by Spanish frigates, which eventually withdrew due to the weather.

The neck of land between the Cooper River and the Ashley River was the home of a new town settlement, which was called “Oyster Point.” Each of the streets intersected at perpendicular angles of 90 degrees. Then, in 1680, Charles Town was settled. It was among the first cities in North America that were actually preplanned. In 1783 it was renamed “Charleston.” Up until 1785, Charleston was the only location for a public records repository in South Carolina. Charleston was also the capital of South Carolina until 1790, when Columbia became the capital.

Trading in deer skins was the first major business in South Carolina. It offered some economic stability in the area, which seemed like a positive thing at the time. However, in 1715, a war between the settlers and the Yemassee Indians broke out. That war was largely caused by the encroachment of the settlers into the Indians’ territory.

In addition to deer skins, South Carolina was also known for creating pitch and tar, as well as other naval supplies. That is part of what caused pirates to frequently come to the South Carolina coast. Pirates were welcome in the 1800s, but their presence became a major source of trouble after the Yemassee Indian War ended.

In June of 1718, four ships sailed in the direction of Charles Town, led by Blackbeard. They stopped ships on a regular basis, taking hostages and trading them for goods, especially medical supplies. In 1717, about 600 free white men (half of the state’s free white male population at the time, petitioned the crown for protection from the pirates. Further dissension in the Charles Town area occurred when it was made clear that the Lords Proprietors’ policies were not sufficient to defend the colony. That led to a revolution occurring in 1719, thanks to a rumor that a Spanish fleet was getting ready to attach Charles Town. The 1719 revolution eventually led to the Crown establishing a provisional royal government to replace the Lords Proprietors in 1721. In 1729, seven of the Lords Proprietors were bought out by the Crown. At that time, the area became known as a royal colony.

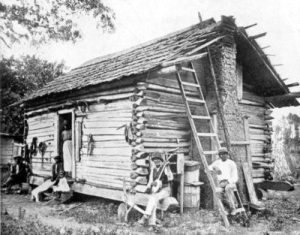

There is a division in South Carolina between the “Low Country” and the “Up-Country.” That division exists from both a topographical standpoint and a cultural standpoint. The fall line, which runs approximately from Cheraw to Camden, to Columbia, to Aiken, represents the topographical division of the state. As far as the cultural division goes, the Low Country is considered to be the area in and around Charleston, including the tidewater region. Low Country residents typically owned indigo or rice plantations, keeping a number of slaves to run the plantations. Up-Country residents, on the other hand, usually had smaller farms and fewer slaves, if any. Charleston was the governmental seat and the Up-Country residents did not like that, often feeling that they were not represented fairly, and often voicing those opinions. There was a distinct lack of local government in the area at the time, which led to many of those complaints.

There were several instances of rebellion against the government by the Up-Country residents of South Carolina between the 1730s and the 1760s. The elitist residents of the Low Country promised that the Up-Country residents would have protection from the Indians, good schools, and churches. However, those all turned out to be empty promises. Up-Country residents became isolated and had to endure a lot of hardships. So, they rarely bothered to go to Charles Town unless they were trying to obtain land by petitioning the government. Then, in 1765, the Stamp Act was passed. Since it applied to everything from playing cards to legal documents, the Low Country residents suddenly found themselves paying more money than they were used to. Suddenly, they needed the support of the Up-Country frontiersmen in order to fight against the Stamp Act.

The 1769 District Circuit Court Act created 7 different judicial districts in South Carolina. The first South Carolina court cases to be tried outside of Charleston were tried around 1772.

South Carolina was extremely split during the Revolutionary War. Those living in and around Charleston wanted to protest the tea importation, especially after the Boston Tea Party took place. Loyalists living in the Up-Country went so far, in November of 1775, as to attack a fort at Ninety-Six. For 7 years, the Revolutionary War was a focal point in South Carolina. In June of 1776, Charleston came under attack from British troops, but they were soon forced to back off. The following month, the Cherokee War began in the Up-Country. In May of 1777, the northwest corner of South Carolina was given up by the Cherokees, but only after militia members from Virginia, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina all worked to defeat the Cherokees.

There were several skirmishes fought in the Up-Country between the Loyalists and the Patriots from 1776 to 1779. However, the Patriots generally had the upper hand. In the midst of those skirmishes, Charleston was once again attacked by the British, in May of 1778. After two years, Charleston surrendered to the British in May of 1780. Then British troops began to lay siege to the Up-Country. In the meantime, Patriot farms were attacked by Loyalists on a fairly regular basis. That caused civil wars to break out in several parts of the state. Patriot guerrilla groups went after both the British and the Loyalists. Eventually, the Patriots forced the British to leave the Up-Country, thanks to the following series of battles: Camden (May 1781), Ninety-Six (May-June 1781), Eutaw Springs (September 1781)

Both the British and the Loyalists withdrew back to Charleston because the Patriots had weakened them so much. Then, on December 14, 1782, the British finally left Charleston. More than 4,000 Loyalists left with the British at that time.

Throughout most of the 1700s, indigo and rice crops supported the economy in South Carolina. However, bounty losses and debts from the Revolutionary War almost destroyed the economy of the state. Luckily, Loyalists who had previously been exiled to the Bahamas returned to the state around that time. They brought with them a type of cotton, which wound up thriving in the state, especially in its southeastern region. When Eli Whitney updated the cotton gin, in 1793, cotton crops led to prosperity in the area.

Growing cotton was a lot like growing indigo or rice in that it required a lot of manual labor. Unfortunately, there were not enough workers to tend the crops. So, in 1803, the state temporarily reopened slave trading. Over the next 5 years or so, 40,000 slaves were imported to the area. Cotton crops slowly expanded to the west, but slavery debates divided the country and tempers were flaring. On December 17, 1860, South Carolina held a convention to discuss its secession from the Union. The state felt threatened by Abraham Lincoln and the growing abolitionist movement in the north.

South Carolina was the first state to ratify the Constitution of the Confederate States of America. It was also the first state where Civil War shots were fired. As a result, it was treated particularly harshly when it was taken by General William T. Sherman’s troops, which was in 1864. The following years were full of economic and racial tension, but the state eventually recovered.

South Carolina Ethnic Group Research

1867 and 1868 were very significant years for African Americans in South Carolina. They gained the vote and, as the majority in the state, they had significant pull for the first time. Those voter registration lists contained lists of freed slaves, which are valuable for researchers.

Many records pertaining to African Americans in South Carolina still exist today. Some of those records include: Free Persons of Color, Slave Lists, Plantation Records, Family Records, Personal Records, Bills of Sale, Account Books, Indentures

Many collections of those documents exist. Some are housed at the College of Charleston, Winthrop College, and the University of South Carolina. Others can be found at the South Carolina Historical Society and the South Carolina Department of Archives and History. Each county kept different records regarding slaves and freed African Americans. Some of the best informational sources for researchers are the property and estate records for each district or county.

- Kenneth M. Stampp, Professor Emeritus, University of California at Berkeley offers one of the best discussions of antebellum plantation records as the introduction to “Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution Through the Civil War,”

- African American Genealogical Research. Rev. ed. Columbia, S.C.: Department of Archives and History, 1997.

- “Naming, Kinship and Estate Dispersal: Notes on Slave Family Life on a South Carolina Plantation, 1786–1833,” William & Mary Quarterly, 3d Series. 39 (1982): 192-211.

- South Carolina’s African American Confederate Pensioners, 1923–1925 (Columbia, S.C.: Department of Archives and History, 1998).

- The Many Faces of Slavery (Columbia, S.C.: Department of Archives and History, 1999), discusses manumission, contracts, maroons, religion, miscegenation, and family relationships.

- James Rose and Alice Eichholz, Black Genesis (1978; reprint, Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2003).

South Carolina History Databases and other Helpful Links

The websites below will provide state-specific details to those in search of information for South Carolina genealogy work.

State Genealogy Guides

[mapsvg id=”13028″]