Wisconsin was once referred to as the “fairest portion of the Great West.” Europeans first came to it in 1634, which New France sent Jean Nicolet to explore the area. He came to Green Bay’s Red Banks on the shores of Lake Michigan that summer. Then he went back to Canada, having been unsuccessful in his mission to find the passage to China, which Samuel de Champlain had sent him to find.

Louis Joliet, who was a map maker (cartographer) and an explorer, came to the area in 1673, along with 6 others. One of them was Father Jacques Marquette. Their exploration helped the French to learn more about the territory that later became the state of Wisconsin. They traveled down the Fox River, followed by the Wisconsin and the Mississippi. They were led by two guides from the Native American tribe known as the Miami. They eventually made it to an area close the the present-day border of Louisiana and Arkansas and stopped in a Quapaw village there.

In 1668, Toussaint Baudry and Nicolas Perrot, who was a Frenchman born around 1644, lived in New France, Canada. They were partners in a trading company. They were invited by the Potawatomi tribe to visit the Green Bay area in 1668. It was not the first or last time that Perrot visited with Native Americans. In fact, he was known for specializing in tribal diplomacy. His efforts led to many useful alliances with Wisconsin tribes throughout the last part of the 1600s.

In 1669, a mission was opened near present-day Brown County by Jesuit Father Claude Allouez. That mission was also a major fur trading post for the French until it ceased operating in 1728. In 1717, Fort Francis was constructed near the Fox River. It was later reconstructed by the British and given the new name of Fort Edward Augustus in 1763. Two years later, Green Bay was settled by Charles de Langlade and his family, making Green Bay the oldest of Wisconsin’s permanent white settlements.

The United States gained control of Wisconsin when the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783. However, the British really controlled the area for quite a while after that. In 1787, Wisconsin became part of the new Northwest Territory. It stayed part of that territory until it became part of Indiana Territory, which was in 1800. Michigan Territory was formed in 1805, but Wisconsin remained part of Indiana Territory. However, all of Wisconsin became part of Illinois Territory on February 3, 1809, with the exception of Door County Peninsula. In 1818, Wisconsin became part of Michigan Territory, after Illinois gained its statehood. In 1836, it became its own territory. Then, in 1848, it finally became a U.S. State.

By 1850, two years after becoming a state, Wisconsin’s population had grown to more than 300,000. Approximately two thirds of the population was born in America, while the other third were foreign-born. Those foreign-born immigrants came from many different countries, including Canada,

England, Switzerland, Germany, Ireland, Wales, The Netherlands and Norway.

Of those born in American who lived in Wisconsin at the time, about 20% of them were born in Wisconsin and the majority of them were children. Those who came from other parts of America were from all over, including the South, the mid-Atlantic region, and New England. People also came from Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, and New York. In fact, as of 1850, there were 68,600 people from New York living in Wisconsin.

One thing that researchers should be aware of about migrants or immigrants to Wisconsin is that most of them came there from their ports of debarkation or their home states. Although, some Dutch and German people did stay in other states before saving up enough money to more to the area. The same goes for the Irish, who came from both Canada and the east coast. It’s also worth noting that those from New England, Pennsylvania, and New York typically made several stops along the way. Those stops can often be traced by looking at the birth records of their children. Those records can be found across the entire Northeast, as well as Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio.

Wisconsin Ethnic Group Research

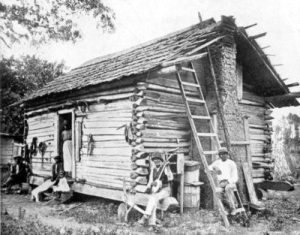

Based on those census records, Wisconsin’s position regarding slavery at the time is clear. In 1840, Racine County was the site of the formation of the first abolitionist society. In 1843, the anti-slavery newspaper, known as Wisconsin Aegis, was published. The Underground Railroad was also a major fixture in the state, especially during the 1850s. It was used to move slaves up into Canada, where they could be free. Wisconsin passed its “personal liberty law” in 1857, which made it difficult for slave owners from other states to recover runaway slaves staying in Wisconsin. Many records have been collected and continue to be collected by the Wisconsin Black Historical Museum. They include papers, photographs, books, and various artifacts.

- “Wisconsin Defies the Fugitive Slave Law: The Case of Sherman M. Booth.” Chronicles of Wisconsin. Vol. 5. Madison, Wis.: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1955.

- African American Newspapers and Periodicals: A National Bibliography. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Negro Slavery in Wisconsin and the Underground Railroad. No. 18. Milwaukee, Wis.: Parkman Club Publications, 1897.

- Papers, 1860–1901. Wisconsin Historical Society. These papers include muster rolls for the 58th Infantry Regiment of U.S. Colored Troops from Wisconsin, MS 62-2651 at Wisconsin Historical Society.

- Wisconsin African American Books

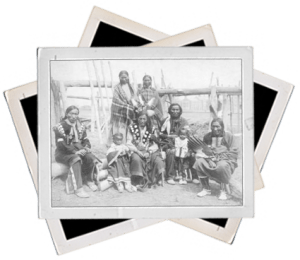

The containment and removal of those tribes caused several problems with tracking Wisconsin Native Americans. There were also problems relating to land sales and treaties because, in some cases, one tribe moved onto a piece of land previously occupied by another. That could mean that multiple records exist for the same piece of land.

From 1829 to 1848, there were 11 treaties with various tribes in Wisconsin. Those treaties caused various tribes to move to other areas. For example the Potawatomi, Kickapoo, and Winnebago moved to Oklahoma, Nebraska, Kansas, and Mexico. Although a few stayed on specific reservations. Some of the Potawatomi stayed in Wisconsin, as did many of the Chippewa and the entire Menominee Nation.

Northern Wisconsin was home to 6 Chippewa reservations in 1984. At that same time, Menominee County was home to a Menominee reservation, and Forest County was home to some federal trust tribal land, on which the Potawatomi resided. The Brotherton tribe has become part of the Stockbridge-Munsee reservation, which is located in Shawano County. Outagamie and Brown counties contain the Oneida reservation. The Winnebago tribe of Wisconsin was never moved to a Nebraska reservation. Instead, they live in various tribal settlements across Wisconsin.

County court records can sometimes contain information about lawsuits between white settlers and Native Americans, most often over land claims. Guardianship records can be found in collections of probate documents. Researchers should also check the annuity rolls and treaty collections held by the National Archives.

Researchers looking for Native American newspapers should consult the Wisconsin Historical Society, which holds the largest collection of such papers in the country.

- Guide to Catholic Indian Mission and School Records in Midwest Repositories (Milwaukee, Wis.: Marquette University Libraries, Department of Special Collections and University Archives, 1984)

- Wisconsin Indians (Revised. Madison, Wis.: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 2002)

- Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15, “The Northeast” (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978–1998)

- Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal (Madison, Wis.: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2001).

- Native American Periodicals and Newspapers, 1828–1982: Bibliography, Publishing Record and Holdings (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1984)

- Wisconsin Native American Books

Other Immigrant American Research – The earliest Europeans to come to Wisconsin were the French-Canadians. They came for both military and fur trading reasons and settled in Green Bay, Prairie du Chien, and other places in the western part of the state. Many of them married Native Americans. More French-Canadians traveled to Wisconsin later on to work in the growing lumber industry there. Other settlers came from New York and other states. It should also be noted that some immigrants to Wisconsin from Canada were not French-Canadian. Many of those immigrants came from the Atlantic provinces and Ontario, while the French-Canadians primarily came from Quebec.

As of 1850, more than 21,000 Irish people were recorded in Wisconsin. They made up the largest foreign group that spoke English in the area at the time. They lived mainly in Wisconsin’s southern counties. Most of them settled in and around Lafayette or Milwaukee counties. The southern counties of Wisconsin were also home to many settlers from English, especially in 1827, when lead mining was becoming popular in the area. Dane, Columbia, and Racine counties all had large English populations. Meanwhile, settlers from Scotland moved into the eastern parts of Wisconsin, and settlers from Wales came to Wisconsin mainly between the 1840s and 1850s. Starting in the late 1830s, large groups of Germans began to immigrate to Wisconsin. The first German colony was established in 1839 near Milwaukee. Records indicate that it may have included as many as 800 people. Around 12% of the population of Wisconsin was made up of first-generation Germans, as of 1850. Researchers should note that the U.S. government distributed leaflets in coastal regions to try to attract Germans to the area starting in the 1840s. A commissioner of immigration was appointed in the 1850s to live in New York and encourage people to migrate to Wisconsin. That occurred due to the passing of a law in 1852. Another branch office opened in Quebec in 1854. Nevertheless, many Germans who came to the area were not enticed by those efforts. Instead, it was letters from family and friends already living in Wisconsin that encouraged them to immigrate to the area. Those letters spoke of freedom and lots of available land.

In 1850, about 33% of all Norwegians living in the United States made their homes in Wisconsin. However, there were not a lot of Norwegians as compared to the numbers of Germans in the area. Milwaukee, Sheboygan, and Brown counties became home to large groups of early Dutch settlers. Some immigrants from Switzerland came to the area in 1834, but more began to move to the area in the 1840s. In fact, to this day the heritage of the original Swiss settlers who came to New Glarus in Green County is still maintained by that village.

Dane county, as the name suggests, was home to many early Danish immigrants, as were Winnebago and Racine counties. They settled in those counties before 1870. A group of immigrants from Iceland came to Wisconsin in the 1870s, settling in Door County, on Washington Island. Wisconsin also became home to groups of immigrants from Poland and Russia. The former settled in the area between 1870 and 1920, while the latter settled in Wisconsin in the 1890s. A group of Russian Jews moved to Milwaukee between 1910 and 1911, while Italians and Finns also came to the area in the early 1900s.

Many Norwegian Records are maintained in Decorah, Iowa by the Norwegian-American Museum. They maintain a division in Madison, Wisconsin. That division can be contacted at the Vesterheim Genealogical Center, 415 W. Main St., Madison, WI 53703, or their website can be viewed online. There are more than 1,800 family histories, 4,000 reels of church records on microfilm, and countless other records in that collection, including passport records and immigrant lists. Some of the records can be accessed through inter-library loan programs.

Fifty-five boxes of personal family papers covering the years of 1841 to 1931 can be found in the Rasmus B. Anderson papers, which are held by the Wisconsin Historical Society. Madison, Wisconsin is the home of the Wisconsin Memorial Library, which has a large collection of files on the United Kingdom and Norwegian history. Some Irish records are available at the Irish Cultural and Heritage Center’s Irish Emigration Library. That collection includes maps of Ireland and microfilmed indexes of sub-denominations.

- The Immigrant Experience in Wisconsin. Boston: G.K. Hall, 1985

- Wisconsin Native American Books

Wisconsin History Databases and other Helpful Links

The websites below will provide state-specific details to those in search of information for Wisconsin genealogy work.

- History of Wisconsin Wikipedia

- Historical Image Collections

- Local History & Biography Articles thousands of historical newspaper articles on Wisconsin people and communities

- Summer rambles in the West

- Inventory of the state archives of Wisconsin: Department of State.

- Summer on the lakes, in 1843

- The western tourist and emigrant’s guide

- The Standard guide, Mackinac Island and northern lake resorts

- The keeper of the gate, or, The sleeping giant of Lake Superior

- Ensign & Thayer’s travellers’ guide through the States of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Iowa and Wisconsin :

- Documents relating to the French settlements on the Wabash

- Autograph letters

- Wisconsin History Books at Amazon.com

State Genealogy Guides

[mapsvg id=”13028″]